Copper Age woman survived two skull surgeries up to 4,500 years ago

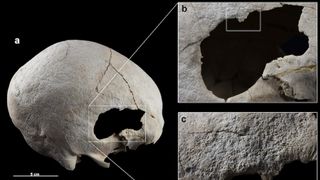

Multiple holes in a skull found at a burial site in Spain were the result of prehistoric surgeries.

Thousands of years ago, a woman underwent two surgeries to her head — and survived both procedures, her skull reveals.

Scientists in Spain made the discovery after analyzing the woman's skeletal remains, which were unearthed at a Copper Age burial site known as Camino del Molino, located in Caravaca de la Cruz in southeastern Spain, according to a study published in the December issue of the International Journal of Paleopathology.

The woman, who was between 35 and 45 years old when she died, was one of 1,348 individuals found at the funerary site, which was used from 2566 to 2239 B.C. However, unlike the other skeletons, her skull showed evidence of a series of trepanations, which are surgical procedures that involved drilling or scraping holes through the skull to expose the dura mater, the outermost layer of tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord, as a form of medical treatment.

Further examination revealed two overlapping holes between her temple and the top of her ear. One opening measured 2.1 inches wide by 1.2 inches long (53 by 31 millimeters), while the second was smaller, at 1.3 by 0.47 inches (32 by 12 mm).

Related: Highest-ranking person in Copper Age Spain was a woman, not a man, genetic analysis shows

Researchers don't think the openings were caused by an injury, based on a few factors. For example, there were no fractures radiating from the lesions, and each hole contained well-defined edges. They concluded that the holes were the remnants of two separate surgeries.

"We identified two distinct holes, resulting from two different interventions," study lead author Sonia Díaz-Navarro, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Prehistory at the University of Valladolid in Spain, told Live Science in an email.

Based on the holes, along with the "oblique orientation of the hole walls," the researchers determined that the trepanations were done using a "scraping technique."

"This involves rubbing a rough-surfaced lithic [stone] instrument against the cranial vault, gradually eroding it along all its edges to create the hole," Díaz-Navarro said. "To perform this surgery, the affected individual likely had to be strongly immobilized by other members of the community or previously treated with a psychoactive substance that would alleviate pain or render them unconscious."

Amazingly, the woman appears to have survived both operations, evidenced by healed bone in her skull. Researchers think she lived several months after the second surgery.

Documentation of prehistoric surgical procedures is a "rare occurrence," especially on this area of the head, known as the temporal region, Díaz-Navarro said. In the Iberian Peninsula, it was more common for trepanations to be performed in the frontal and parietal (top) regions of the skull.

The risks of operating on the temporal region included "inherent challenges associated with accessing this area through the scalp," she said. This region in particular contains numerous blood vessels and muscles that are vulnerable and could easily bleed out during surgery.

However, prehistoric trepanations using the scraping technique were far more successful — and safer — than drilling. Ancient surgeons generally did not damage the meninges or the brain, lowering the risk for potential post-surgical infections, she said, adding that using sterile instruments and plants with natural antibiotic properties could help curb any infection.

Unfortunately, researchers aren't sure why the woman had the surgery in the first place. Even though her skeleton did show healed rib fractures and some dental caries, these afflictions were likely unrelated.

"The high prevalence of traumatic injuries documented in the skeletons from Camino del Molino leads us not to rule out the possibility that the surgery may have been performed as a result of trauma," she said. The surgery could have eliminated any evidence of bruising or incisions, and damaged bone fragments may have been removed during the procedure.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Jennifer Nalewicki is a Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Most Popular

By Conor Feehly

By Harry Baker