The longest-living animals on Earth

The longest-living animals can survive for centuries and millennia, even pausing the aging process altogether. Here are the longest-living animals in the world.

The longest-living animals are equipped with traits to hold off, and sometimes even stop or reverse, the aging process. While humans may have an "absolute limit" of 150 years, this is just a blink of an eye compared with the centuries and millennia that some animals live through.

The true age champions live in water, often at great depths where conditions are stable and consistent. Scientists can't record the birth and death of every member of a species, so they typically estimate maximum life spans based on what is known about a species' biology. From old to oldest, here are 12 of the longest-living animals in the world today.

Related: The secrets to extreme longevity may be hiding with nuns... and jellyfish

12. Seychelles giant tortoise: 190+ years old

Tortoises are famed for their longevity. The oldest living land animal is a 190-year-old Seychelles giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea hololissa) named Jonathan. The tortoise lives on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean after having been brought there by people from the Seychelles in 1882. Jonathan's age is an estimate, but a photograph of him taken between 1882 and 1886 shows he was fully mature — at least 50 years old — in the late 19th century, Live Science previously reported.

On Jan. 12, 2022, Guinness World Records announced that Jonathan was the oldest tortoise ever. "He is a local icon, symbolic of persistence in the face of change," Joe Hollins, Jonathan's veterinarian, told Guinness World Records at the time.

Giant tortoises need to live a long time so they can breed repeatedly and produce plenty of eggs, because many of their eggs are eaten by predators. Their ability to quickly kill off damaged cells that normally deteriorate with age may help tortoises live so long, Live Science previously reported.

Related: Tiny white tortoise baby is the 'first of its kind'

11. Red sea urchins: 200 years old

Red sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus franciscanus) are small, round invertebrates covered in spines. They live in shallow coastal waters off North America from California to Alaska, where they feed on marine plants, according to Oregon State University. Researchers used to assume that red sea urchins grew quickly and had modest life spans of up to about 10 years, but as scientists studied the species in more detail, they realized these urchins continue to grow very slowly and, in some locations, will survive for centuries if they can avoid predators, disease and fishers.

The red sea urchins found off Washington and Alaska probably live more than 100 years, and the longest-living individuals in British Columbia, Canada, may be around 200 years old, according to a 2003 study published in the journal Fishery Bulletin.

Related: Mysterious 'blue goo' at the bottom of the sea stumps scientists

10. Bowhead whale: potentially 200+ years old

Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) are the longest-living mammals. The Arctic and sub-Arctic whales' exact life span is unknown, but stone harpoon tips found in some harvested individuals prove that they comfortably live over 100 years and may live more than 200 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The whales have mutations in a gene called ERCC1, which is involved with repairing damaged DNA, that may help protect the whales from cancer, a potential cause of death. Furthermore, another gene, called PCNA, has a section that has been duplicated. This gene is involved in cell growth and repair, and the duplication could slow aging, Live Science previously reported.

Studying these long-lived whales could provide hints about how to prolong human life. "My own view is that different long-lived species use different tricks to evolve long life spans, and there aren't many genes in common," João Pedro de Magalhães, an expert in aging science at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., previously told Live Science. "But you do find some common pathways, so there may be common patterns."

Related: Natural rates of aging are fixed, study suggests

9. Rougheye rockfish: 200+ years old

The rougheye rockfish (Sebastes aleutianus) is one of the longest-living fish, with a maximum life span of at least 205 years, according to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. These pink or brownish fish live in the Pacific Ocean from California to Japan. They grow up to 38 inches (97 centimeters) long and eat other animals, such as shrimp and smaller fish, according to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, an independent advisory panel that assesses the statuses of species threatened with extinction in Canada.

A 2021 study published in the journal Science looked at the genomes of 88 rockfish species, including rougheye rockfish, and found genetic calling cards for longevity, including DNA repair pathways that may help ward off cancers. A longer life span allows the rockfish to grow larger and produce more young.

Related: Is fish caught off Alaska 200 years old?

8. Freshwater pearl mussel: 250+ years old

Freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera) are bivalves that filter particles of food from the water. They live mainly in rivers and streams and can be found in Europe and North America. The oldest known freshwater pearl mussel was 280 years old, according to the World Wildlife Fund for Nature. These invertebrates have long life spans thanks to their low metabolism.

Freshwater pearl mussels are an endangered species. Their population is declining due to a variety of human-related factors, including damage and changes to the river habitats they depend on, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Related: Seattle mussels test positive for opioids

7. Greenland shark: 272+ years old

Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) live deep in the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans. They can grow to be 24 feet (7.3 meters) long and have a diet that includes a variety of other animals, including fish and marine mammals such as seals, according to the St. Lawrence Shark Observatory in Canada.

A 2016 study of Greenland shark eye tissue, published in the journal Science, estimated that these sharks can have a maximum life span of at least 272 years. The biggest shark in that study was estimated to be about 392 years old, and the researchers suggested that the sharks could have been up to 512 years old, Live Science previously reported. The age estimates came with a degree of uncertainty, but even the lowest estimate of 272 years still makes these sharks the longest-living vertebrates on Earth, Julius Nielsen, a researcher at Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, previously told Live Science.

Related: 100-year-old Greenland shark that washed up on UK beach had brain infection, autopsy finds

6. Tubeworm: 300+ years old

Tube worms are invertebrates that live on the ocean floor. Bacteria in their tubes create sugars from chemicals, which they absorb as food, according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Dive and Discover website. Some tube worms live around hydrothermal vents, but the longest-living species are found in colder, more stable environments called cold seeps, where chemicals spew from cracks or fissures in the seafloor, according to the Exploring Our Fluid Earth website hosted by the University of Hawaii.

A 2017 study published in the journal The Science of Nature found that Escarpia laminata, a cold-seep species of tube worm in the Gulf of Mexico, regularly lives up to 200 years, and some specimens survive for more than 300 years. Tube worms have a slow metabolism and few natural threats (such as predators), which has helped these creatures evolve such long life spans.

Related: Wonderland of iridescent worms and hydrothermal vents found off Mexican coast

5. Ocean quahog clam: 500+ years old

Ocean quahog clams (Arctica islandica) inhabit the North Atlantic Ocean. This saltwater species can live even longer than the other bivalve on this list, the freshwater pearl mussel. One ocean quahog clam found off the coast of Iceland in 2006 was 507 years old, according to National Museum Wales in the U.K. The ancient clam was nicknamed Ming because it was born in 1499, when the Ming dynasty ruled China (from 1368 to 1644).

"In the colder waters surrounding Iceland the Ocean Quahog has a slower metabolism and so grows slowly and may even live for longer than 507 — scientists just haven't found an older one yet!" Anna Holmes, curator of invertebrate biodiversity (bivalves) at National Museum Wales, wrote on the museum's website in 2020.

Related: 1 billion sea creatures cooked to death in Pacific Northwest

4. Black coral: 4,000+ years old

Corals look like colorful, underwater rocks and plants, but they are actually made up of the exoskeletons of invertebrates called polyps. These polyps continually multiply and replace themselves by creating a genetically identical copy, which over time causes the coral exoskeleton structure to grow bigger and bigger. Corals are therefore made up of multiple identical organisms rather than being a single organism, so a coral's life span is more of a team effort.

Deep-water black corals are among the longest-living corals. Black coral specimens found off the coast of Hawaii have been radiocarbon dated to be 4,265 years old, Live Science previously reported.

Related: We finally know why Florida's coral reefs are dying, and it's not just climate change

3. Glass sponge: 10,000+ years old

Sponges are made up of colonies of animals, similar to corals, and can also live for thousands of years. Glass sponges are among the longest-living sponges on Earth. Members of this group are often found in the deep ocean and have skeletons that resemble glass, hence their name, according to NOAA.

A 2012 study published in the journal Chemical Geology estimated that a glass sponge belonging to the species Monorhaphis chuni was about 11,000 years old. Other sponge species may be able to live even longer.

Related: 300-year-old Arctic sponges feast on the corpses of their decaying, extinct neighbors

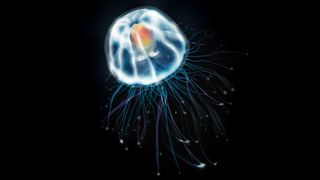

2. Turritopsis dohrnii: potentially immortal

Turritopsis dohrnii is called the immortal jellyfish because it can potentially live forever. Jellyfish start life as larvae before establishing themselves on the seafloor and transforming into polyps. These polyps then produce free-swimming medusas, or jellyfish. Mature T. dohrnii are special in that they can turn back into polyps if they are physically damaged or starving, according to the American Museum of Natural History, and then later return to their jellyfish state.

The jellyfish, which are native to the Mediterranean Sea, can repeat this feat of reversing their life cycle multiple times and therefore may never die of old age under the right conditions, according to the Natural History Museum in London. T. dohrnii are tiny — less than 0.2 inch (4.5 millimeters) across — and are eaten by other animals, such as fish, or may die by other means, thus preventing them from actually achieving immortality.

Related: Thousands of jellyfish swarm near Israel, mesmerizing images reveal

1. Hydra: potentially immortal

Hydra is a group of small invertebrates with soft bodies that slightly resemble jellyfish and, like T. dohrnii, have the potential to live forever. These invertebrates are largely made up of stem cells, which continually regenerate through duplication or cloning, so these animals don't deteriorate as they get older. They do die under natural conditions because of threats such as predators and disease, but without these external dangers, they could keep regenerating forever.

"They don't seem to age, so potentially, they are immortal," Daniel Martínez, a biology professor at Pomona College in Claremont, California, who discovered the hydra's lack of aging, previously told Live Science.

Related: Here's the secret to how 'immortal' hydras regrow severed heads

Originally published on Live Science Aug. 16, 2021, and republished Oct. 28, 2022.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Patrick Pester is a freelance writer and previously a staff writer at Live Science. His background is in wildlife conservation and he has worked with endangered species around the world. Patrick holds a master's degree in international journalism from Cardiff University in the U.K.

Most Popular

By Conor Feehly

By Harry Baker