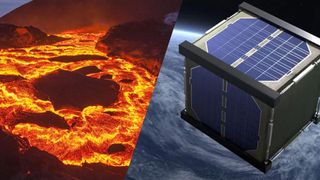

Science news this week: Supervolcanoes and a wooden satellite

Nov. 19, 2023: Our weekly roundup of the latest science in the news, as well as a few fascinating articles to keep you entertained over the weekend.

This week in science news, we found four supervolcano "megabeds," learned that the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way is spinning at near top speed, and debunked claims around tiny "alien" spherules discovered last year.

Researchers discovered four massive supervolcano megabeds that had been resting at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea for up to 40,000 years. These deposits, between 33 and 82 feet (10 to 25 meters) in thickness, point to catastrophic events that have struck Europe every 10,000 to 15,000 years.

While Iceland's rumbling volcano isn't likely to be as impressive, the country is nonetheless bracing for an imminent volcanic eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula. The residents of Grindavík, in southwest Iceland, were evacuated after three sinkholes appeared in their town. Seismic activity began Oct. 25, and the Icelandic Met Office confirmed there was a 9.3-mile-long (15 kilometers) "magma tunnel" stretching from Sundhnúk in the north down to Grindavík, and then into the sea — with experts suggesting an eruption could take place anywhere along it.

While we await news from below, looking to the skies, NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency are planning to launch the world's first wooden satellite as soon as next year. Called LignoSat, the mug-size satellite is made from magnolia wood and designed to test the feasibility of using the biodegradable material for future satellites.

Somewhat farther afield, we now know Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, is spinning at almost its maximum possible speed, and dragging space-time along for the ride. Scientists have also been drilling into the disruptive effects of the most powerful gamma-ray burst since the Big Bang. The massive gamma-ray burst, which was first detected in October 2022 and occurred when a star located more than 2 billion light-years away exploded, severely disrupted Earth's ionosphere. Researchers will now probe whether the "BOAT" — short for "brightest of all time" — gamma-ray burst influenced any of Earth's mass extinction events.

Back on Earth, scientists followed a long trail of crabs to a new hydrothermal vent in the Galápagos. The field spans more than 98,800 square feet (9,178 square meters) in the Galápagos Spreading Center. In other crab news, scientists learned this week that the crustaceans evolved to migrate from marine to land habitats between seven to 17 times, and even evolved to return to the sea on two or three occasions. Moving from the tiny to the gargantuan, scientists showed that elephants give each other names in the form of low-pitched "complex" rumbles, making them the first known nonhuman animals to do so.

Speaking of named animals, pets (and their food) may be the source of two human outbreaks of Salmonella.

In better news, scientists have developed "bionic breasts" to restore sensation for breast cancer survivors. And in a small-but-successful trial, researchers used CRISPR to edit the genomes of people with familial high cholesterol. Casting our eye to the future, scientists recently demonstrated a prototype for a tiny, shape-shifting robot that could one day perform automated surgery inside the human body.

—'Student of Games' is the 1st AI that can master different types of games, like chess and poker

—From arsenic to urine, archaeologists find odd artifacts on museum shelves

—'Bouncing' comets may be delivering the seeds of life to alien planets, new study finds

—The brain may interpret smells from each nostril differently

But we also made several key discoveries in our quest to better understand the past, with German archaeologists unearthing the foundations of two temples at a former Roman camp and a separate team digging up a 4,000-year-old tomb in Norway that may have contained the region's first farmers. This week, we also realized Stone Age Europeans were hunting with spear-throwers more than 30,000 years ago, which is roughly 10,000 years earlier than we previously thought.

And finally, the curious, colorful metal spherules dug out of the Pacific Ocean earlier this year aren't mysterious alien relics from outer space, as previously theorized, but rather the byproduct of burning coal on Earth.

Follow Live Science on social media

Want more science news? Follow our Live Science WhatsApp Channel for the latest discoveries as they happen. It's the best way to get our expert reporting on the go, but if you don't use WhatsApp we’re also on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Flipboard, Instagram, TikTok and LinkedIn.

Picture of the week

This stunning NASA satellite image shows Eurasia's tallest volcano, Klyuchevskoy, throwing a 1,000-mile-long (1,600 km) cloud of dust and ash into the air. It's been continuously erupting since mid-June, but a massive volcanic explosion on Nov. 1 launched a gigantic torrent of smoke and ash that reached 7.5 miles (12 km) above Earth's surface. The river of smoke prompted the Kamchatka Volcanic Eruption Response Team to raise the aviation alert level to red — the highest possible level — and to ground planes in the area.

Although hard to distinguish from the cloud, the plume stretches right across this image from Klyuchevskoy into the Pacific Ocean. While this trail of smoke and ash was enormous, it is still far from the largest eruption plumes ever seen. This outburst lasted only a few days, and Klyuchevskoy may have stopped erupting altogether.

Sunday reading

- Do lemmings really jump off cliffs, or is that just an urban myth?

- 'It's really quite remarkable': Elephant expert Ross MacPhee on why elephant noses are so remarkable.

- Why are dogs, especially puppies, in endless pursuit of their tails?

- This is what happens to cats, and their digestive systems, when they get too fat.

- Why are most planets and moons (mostly) spherical?

- Watch an incredibly rare dreamer angelfish swim like a shadow in the deepest depths of the sea off the California coast.

Live Science long read

We were especially struck by the message of noted climatologist Michael Mann, who argues in a recent opinion piece that there is still time to avert climate change. The upshot? For decades, scientists have struggled to communicate climate risk in the face of deep uncertainty.

But rather than de-emphasizing climate risk, scientists have potentially been guilty of the opposite: failing to communicate that we can still stop global warming in its tracks.

State-of-the-art climate models make it clear that once humans stop spewing carbon into the atmosphere, there is near-zero "thermal inertia," which means warming stops. That means there's still time for humans to cut emissions and avoid reaching the critical 1.5-degree-Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) threshold.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Keumars is the technology editor at Live Science. He has written for a variety of publications including ITPro, The Week Digital, ComputerActive and TechRadar Pro. He holds a BSc in Biomedical Sciences, and has worked as a technology journalist for more than five years.

Most Popular

By Harry Baker

By Tom Metcalfe

By Emily Cooke

By James Frew